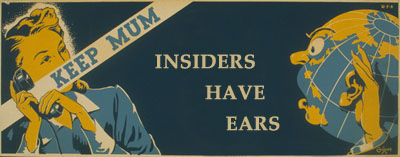

Insider Threat - A Touchy Security Topic

The insider vs. outsider threat debate may be less relevant as external attackers increasingly compromise employee workstations via social engineering and exploit kits—outsiders become insiders. Organizations should treat insiders as untrusted entities to the extent practical, implementing least privilege and monitoring.

Information security professionals often disagree on the prevalence of insider threat with respect to attacks that originate from outside of the organization. Let’s explore why that might be the case and what we can learn from the debate.

Insider threat is often used as the universal boogie man to justify information security expense, especially in situations where risks are difficult to quantify.

How prevalent are the attacks that are conducted by the organization’s own workforce in comparison to the threats that originate from external entities? The infosec community has been debating this topic for some time, even though the answer might be becoming less and less useful.

Why We Care About Insider Threat

Insider threat is generally posed by employees or contractors who’ve been granted access to valuable data. Insiders are assumed to understand inner-workings of the company to determine what data is valuable, where it resides, and how to bypass the security measures that protect it. In some cases, insiders already have access to sensitive information by the nature of their job function, and only need to determine how to exfiltrate the data. The discussion orients around the idea that the majority of information security threats come from insiders, even though there seems to be no reliable data to support this claim. (Richard Bejtlich traced the origin of this meme to an old statistic published by FBI.)

I suspect the issue keeps resurfacing because people are preoccupied with the idea that they might be “betrayed” by their own colleagues. Moreover, there is an implication that by the nature of access granted to them, insiders can cause more damage than outsiders. For instance, the tremendous effect that insiders can have on data security was highlighted by the leakage of US diplomatic cables in the Cablegate affair.

Data About Insider Threat

According to the the (now somewhat dated) 2007 E-Crime Watch Survey conducted by CSO Magazine, responders believed that 26% of the security events were caused by insiders (58% by outsiders; 17% unknown). This finding was almost identical to that of the prior year’s survey. “When asked who caused more damage (in terms of cost or operations), results were fairly close (insiders 34%, outsiders 37%, unknown 29%).”

Verizon’s 2010 Data Breach Investigations Report attributed the majority of breaches and almost all data stolen in 2009 to outsiders. However, insider-caused breaches were more common in cases handled by the US Secret Service. Overall, 48% of data breaches were caused by insiders, according to the study. How were the breaches caused by insiders discovered? According to the 2008 Insider Threat Study by US Secret Service and CERT,

“Most of the insider incidents were only discovered through manual (non-automated) detection of an irregularity or failure of an information system. … Most insiders’ actions were triggered by a specific work-related event … [and] the majority of insiders planned their activities in advance.”

Only “some insiders had prior arrests,” so it’s background checks would not have been very effective in curtailing the attacks.

Outsiders == Insiders

Ultimately, it doesn’t matter whether insider threats are more prevalent than outsider threats, if we agree that both vectors result in breaches that—at least in the short term—can have costly implications. External attackers have been shifting tactics to compromise systems used by internal employees and contractors. This typically involves the use of social engineering and client-side exploit kits to gain access to an employee’s or contractor’s workstation. Such attacks can be so effective, that an outsider can easily become an insider. These breaches are caused by outsiders; however, they use insiders as the conduit for the attack. As organizations adjust their security programs, they will do well by treating insiders as entities that are untrusted to the extent that’s practical. This implies implementing controls such as separation of duties, least privilege, incident response and monitoring of actions taken by authorized parties. This note is part of my 3-post series on the subjects that tend to touch a nerve among many security folks. Other posts look at Advanced Persistent Threat (APT) and Return on Investment.