When Does a Suspicious Event Qualify as a Security Incident?

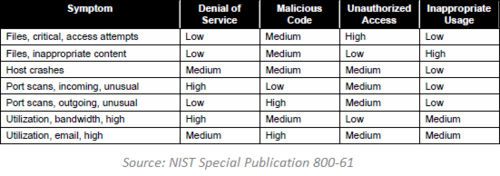

Distinguishing suspicious events from actual incidents is challenging—panicking at every alert wastes resources, while ignoring meaningful ones allows escalation. Each organization must decide its threshold based on staff size, IR capabilities, budget, and risk appetite. NIST 800-61 offers a diagnostic matrix to help.

One of the many challenges of incident response (IR) is distinguishing a series of suspicious events from an actual security incident. Start panicking about every IDS or anti-virus alert, and you’ll not only develop hypertension, but will also waste the time of your staff. Ignore meaningful events, and you’ll miss the opportunity to identify an issue before it escalates into a major breach.

Much of the IR and forensics advice assumes that the person wishes to take a deep dive into the system that is believed to be compromised. The initial responders (e.g., system administrators or end-users) should be taught the steps to take when troubleshooting a computer issue. They should also be instructed what criteria they should use before involving IR specialists.

A good starting point for tackling this challenge is the Incident Analysis section of NIST Special Publication 800-61, Computer Security Incident Handling Guide. It highlights the difficulty of being able to weed through the thousands or millions of indications per day to find the few security incidents that require a thorough investigation. The document explains:

“Some incidents are easy to detect, such as an obviously defaced Web page. However, many incidents are not associated with such clear symptoms. Small signs such as one change in one system configuration file may be the only indications that an incident has occurred. In incident handling, detection may be the most difficult task. Incident handlers are responsible for analyzing ambiguous, contradictory, and incomplete symptoms to determine what has happened.”

NIST 800-61 offers a sample matrix that can help the less-experienced staff perform the initial survey of the situation:

The process of qualifying an incident involves examining a series of indicators to see whether they exceed a certain threshold that marks the lose border between suspicious events and a security incident. The indicators might take the form of security alerts, end-user reports to help-desk, performance metrics, operational anomalies and sometimes even a gut feeling.

The trick is this: Each organization needs to decide for itself where it wishes to draw the threshold, based on the size of its security staff, IR capabilities, budget restrictions and appetite for risk. Unfortunately, doing this requires being proactive about incident response, which means very few organizations will have the discipline to accomplish this before they have to deal with a major breach.

Related: