Malware analysts often need to share samples with each other. This might involve sending malicious files as password-protected email attachments or providing a link where the specimen might be downloaded. Because of the risks and the associated security precautions, sharing malicious program artifacts with other researchers can be tricky. Below are some considerations for engaging in such activities. See the end of this post for the summary of advice on sharing malware samples.

Password-Protecting the Archive

The most common way of sharing a malware sample with another researcher involves embedding the malicious file in a zip archive that has been protected with the password "infected". Password-protecting the file aims at getting the specimen past antivirus scanners and makes it harder for the recipient to inadvertently infect their system.

When sharing malware samples with other researchers, what password do you use for the archives?

— Lenny Zeltser (@lennyzeltser) March 19, 2016

The informal poll I conducted on Twitter confirmed the use of "infected" as the most common password, which has long been considered the industry standard. It was followed by the password "malware" as the distant second, which happens to be my choice for several reasons:

- Researchers are so used to the password "infected", that they might type it without giving it a second thought. I prefer the recipient to give explicit consideration to the nature of the file they are about to extract from the archive.

- Antivirus tools know about the password "infected" and can use it to extract and scan the archive's contents. This action can cause unnecessary alarms and can prevent the sample from reaching the intended recipient.

The classic problem with "infected" was outlined by Brian Baskin, who noticed that Gmail was blocking access to email attachments that contained malware zip'ed with that password. This behavior occurred due to the automated actions performed by the antivirus engine used by Google to scan email attachments. Google Drive appears to automatically try "infected" to scan password-protected zip files, and will flag them accordingly, stating "Sorry, this file is infected with a virus" and "Only the owner is allowed to download infected files."

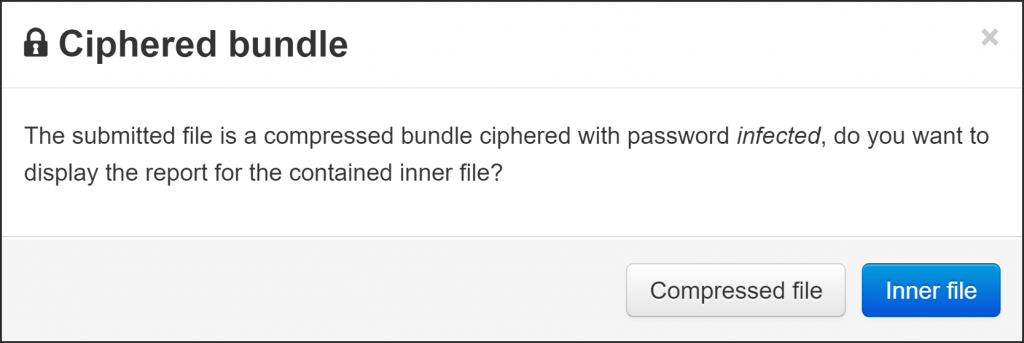

On the other hand, using the password "infected" is convenient when uploading the sample to third-party tools that know about this common practice. For instance, VirusTotal automatically tries this password when you upload a zip'ed file to this popular malware-researching site, as shown in the screenshot below.

Using a less common password increases the chances that the sample won't be blocked or flagged when you share it with someone, though this approach is not without fault.

Malware Attachments vs. Download Links

Email gateways might be configured to block messages that contain password-protected archives, regardless of the password used to protect them. Rather than sending the malware archive as an email attachment, consider uploading it to a website from which the other researcher will be able to download it.

You could upload the file to a malware-specific site, such as VirusBay, Hybrid Analysis or VirusTotal, then send the fellow analyst a link or simply specify the hash value of the file. You might not even need to upload the specimen to such repositories, since they might already contain the specimen. If uploading the sample to such sites, recognize that you are implicitly granting access other individuals access to this potentially sensitive asset.

If using a general-purpose file-sharing service, first confirm that doing this doesn't violate the service's terms of use. The malware research blog Contagio had to move to its samples from Mediafire after Google Safe Browsing services notified Mediafire that the Contagio account was hosting "harmful" files there. As the result, "Mediafire suspended public access to Contagio account." Contagio ended up moving its samples to a Dropbox Business account. (I've been using private Google Drive links for sharing samples without problems so far.)

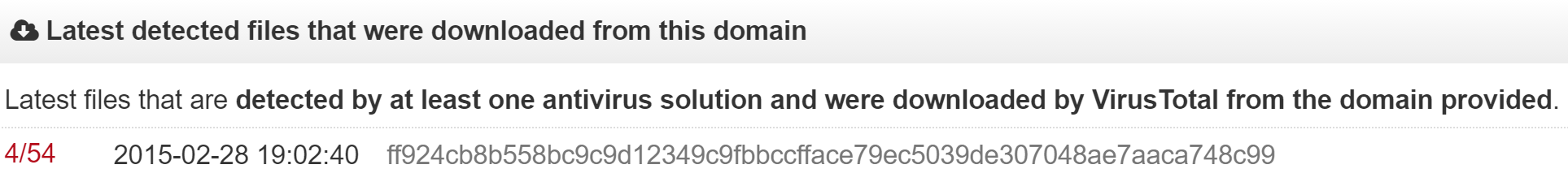

I encountered a slight issue hosting a malware sample that I originally zip'ed and protected with the password "infected". The sample accompanied my Introduction to Malware Analysis webcast and resided on my web server. While the file didn't affect the ranking on my site on commonly-used blacklists, searching for my domain name on VirusTotal some time ago did highlight the presence of this known malicious file on my server, which could've had an adverse effect on my site's rating at some point.

I should've used a different password for that file. Moreover, I should have avoided using zip as the archival algorithm because it doesn't cloak the archive's contents as well as some alternatives.

Zip vs. Other Archival Formats

It's convenient to use zip when sharing malware samples, because this format is supported by most decompression utilities. However, this file format exposes several attributes about the original file that could be used to flag it as malicious and, therefore, interfere with the sharing objective. The standard zip algorithm doesn't conceal names of the archived files even when they've been password-protected. It also reveals CRC checksums of the archived files, which could be used to detect that the zip'ed file contains malicious contents.

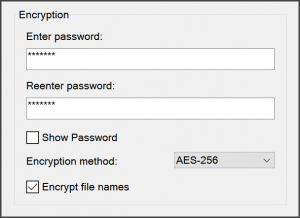

One archival format that is relatively popular among malware researchers is 7-Zip. This open source tool, available for most platforms, gives you the option of encrypting file names when password-protecting the archive. The command-line version of the tool calls this "archive header encryption," which you can accomplish using the -mhe=on parameter. This option is usually turned off by default.

Hashes and Other Considerations

Email gateways, web security and other defenses might block access to password-protected archives that they cannot scan. In these situations, your best option might be to share the sample with the researcher offline, perhaps by mailing the person a USB key that contains the archived malware specimen.

Regardless of how you share the malware sample, it's a good idea to specify the hash of the malicious file, so the analyst can confirm the integrity of the file they received from you. It's common to see MD5 used for such purposes. However, given the possibility of hash collisions, it's better to employ SHA256 as the hashing algorithm.

Before sharing a malware sample with other researchers, make sure they actually expect to receive the malicious specimen. Check with them which sharing method will work best for them. Oh, and before releasing the specimen to someone outside your organization, make sure you're allowed to share this potentially-sensitive file with a third party.

Tips for Sharing Malware Samples

Here's the summary of the recommendations that I outlined above for sharing malware samples with other researchers:

- Confirm for yourself that your employer or client obligations don't prohibit you from sharing the specimen.

- If practical, ask the recipient regarding the approach they prefer to use for receiving the file.

- Don't send the malware sample as a normal file. Instead, password-protect it inside an archive.

- The zip format is frequently used, but you should consider using the 7-Zip format to better conceal the archive's contents.

- The password "infected" is frequently used, but you should consider using a less common password, such as "malware".

- Rather than emailing the specimen as an attachment, consider sending the researcher a link where they could download the file.

- Specify the hash of the malware sample using a modern algorithm such as SHA256, so the recipient can confirm that they obtained the right file.

- Confirm with the recipient that they successfully retrieved the malware sample that you shared with them.

On a related note, if you're wondering where to obtain malware samples, take a look at my Malware Sample Sources for Researchers page.