If you've been working in information security—or IT in general—for a while, you might consider yourself an expert in some aspect of the field. Or maybe you were in a position to hire a seasoned consultant to assist with advanced tasks you could not handle yourself. Whether benefiting from your own proficiency or someone else's, tread carefully: Experts are more likely than non-experts to overestimate their knowledge, according to researchers at Cornell and Tulane Universities.

Claiming Impossible Knowledge

The Scientific American article on the topic clarifies that "self-proclaimed experts are more likely to fall victim to a phenomenon known as overclaiming, professing to know things they really do not." Earlier research already confirmed that people have a hard time differentiating what they know from what they do not. The latest findings indicate that this tendency is more pronounced in the areas where the individuals claim to have expertise.

Participants in the recent study were asked to rate their proficiency in a field such as geography or personal finance. They were then asked to rate their own knowledge of terms in that field. Some of the terms were real. Some were made up. The researchers discovered that self-perceived expertise "positively predicted claiming knowledge of nonexistent domain-related terms." Warning the participants that some of the items were bogus, "did not alter the relationship between self-perceived knowledge and overclaiming, suggesting that self-perceptions were prompting mistaken but honest claims of knowledge."

Don't Take Expertise at Face Value

The experts in the study were not lying about possessing impossible knowledge. They seemed convinced that the terms were real. Therefore, when engaging experts, recognize that they might be unable to critically assess the quality of their knowledge. This means being (or aiming to become) an educated consumer of advice and services, knowing how to ask critical questions and having a meaningful discussion that helps eliminate poor results or weak recommendations.

In the context of information security, this means:

- If your role involves overseeing the company's security program, develop or maintain at least some technical skills. Otherwise, you'll be at the mercy of other people's advice and interpretation without the ability to spot inconsistencies, omissions, lies and mistakes.

- When seeking external services, take the time to understand your needs, rather than letting the third party dictate the scope of work. For instance, if you're commissioning a security assessment, you determine your objectives, desired scope and likely constraints. (The Security Assessment RFP Cheat Sheet provides a reasonable starting point.)

- When reading industry trends or analyst reports, understand the methodology used by the authors. For example, many security vendors share their perspectives in the form of blog posts and whitepapers; you should assess whether their methodology is sufficiently strong and what incentives drive their writing before accepting their conclusions.

I'm not encouraging being combative in the face of expert advice. We should be curious, knowledgeable, and engaging when interacting with people who possess more knowledge in some area than we do. (Informed skepticism—good. Aggressive stubbornness—bad.)

Sharing Your Own Expertise

Cognitive biases affect all of us, sometimes even when we know that we might be influenced by them. If you possess expertise in some field, structure your actions and communications in a way that accounts for such limitations. This might involve the following:

- Seek feedback from mentors and peers. We tend to be bad at seeing our own mistakes, don't know what we don't know, and apparently have a tendency to believe in possessing impossible knowledge. For instance, if authoring a security trends report, ask others to review it before you finalize it. Doing this requires possessing a circle of people you trust to comment on the draft version of your work.

- Encourage the recipients of your advice or services to ask questions and critique you. Invest in educating them, so that the resulting discussion is fruitful and mutually-beneficial. For example, if documenting the results your security assessment, ask the client whether there are additional areas should you have explored, or whether some of your findings might be invalid.

- Be open to changing your perspective. That's hard, because sharing expertise require a certain degree of self-confidence. Yet, nobody is perfect. Accept the fact that once in a while you will be wrong and be willing to make adjustments accordingly. Don't accept feedback blindly, but review it to decide whether it can improve your position or strengthen your deliverable.

Information security is a discipline comprised of many sub-fields. Most people cannot be experts in all of them, but those who work hard, can develop deep knowledge in some areas, be they application security, network defense, incident response, etc. We need experts who not only possess the expertise, but also think critically about their knowledge.

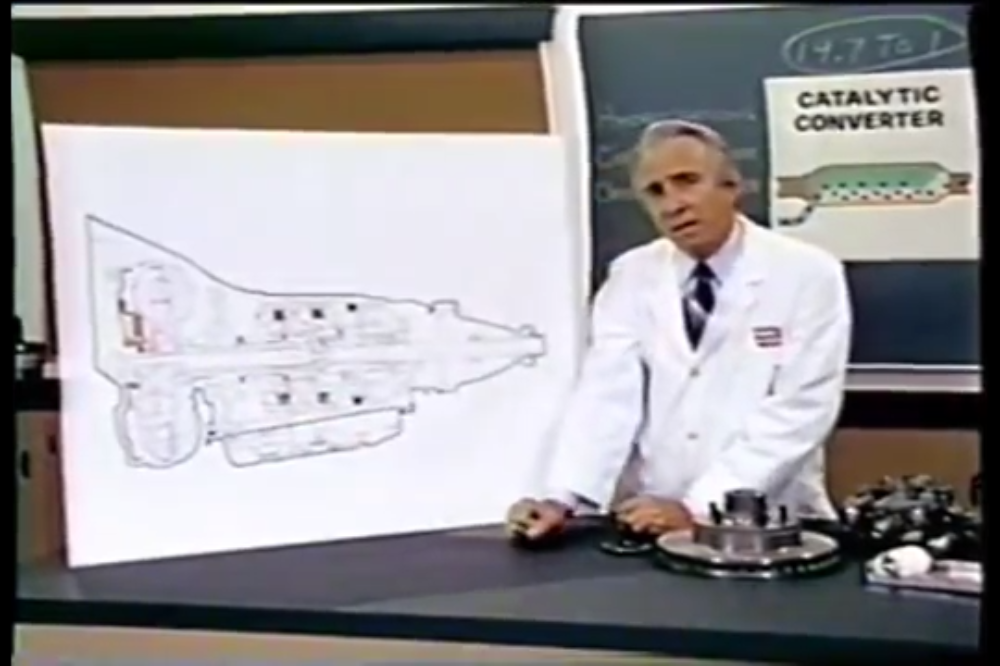

Turbo Encabulator

Speaking of nonexistent domain-specific expert terms, how could I not include a pointer to the classic Turbo Encabulator video?