Though some malicious software can operate autonomously, many specimens are programmed to stay in touch with the attacker to obtain operating instructions. The mechanism that such bots use for communicating their operators is called command and control (C&C or C2). C&C channels can take the form of IRC chatter, peer-to-peer protocols, generic HTTP traffic, and so on. Several malware samples that appeared recently have also used social media for C&C.

Why Use Social Media for C&C?

From the perspective of a malware author, there are several reasons for considering the use of social media venues, such as Facebook, Twitter or blogs for implementing the C&C mechanism:

- The authors “hang out” on social networking sites on routine basis, which puts social media on the top of their minds.

- Interactions with social networking sites can be easily automated not only through the use of “old school” HTML parsing, but also by using powerful API capabilities of such sites.

- Accessing social networking sites involves the use of Internet-bound HTTP or HTTPS connections, which are rarely blocked.

- Defenders of corporate networks are unlikely to notice the offending traffic in the large volumes of other Internet-bound sessions.

Social Media Profiles for Instructions

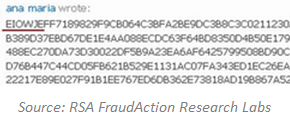

One example of malware using social media, though not social networking sites, for command-and-control was documented by RSA. In that case, a banking trojan retrieved the Windows Live profile set up specifically for C&C. The profile was registered to “ana maria” and contained encrypted instructions from the attacker.

According to RSA, the trojan retrieved and parsed the profile's contents after infecting a computer. It searched the profile for the string EIOWJE, which “signified the starting point of the malware's configuration instructions.”

Twitter for URLs to Additional Downloads

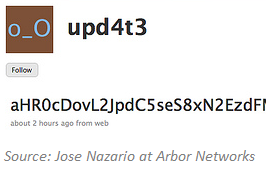

Jose Nazario documented an early example of malware using Twitter for obtaining instructions. The attacker set up a Twitter account called “upd4t3”, on which he published Base-64 encoded text. The malicious program, running on the victim's computer used the RSS feed to the Twitter account to retrieve the updates. The updates, once decoded, included Bitly-shortened URLs where additional malicious programs resided.

Jose also noticed the attacker using other social media sites, namely Jaiku and Tumblr, to issue instructions to the bot.

Twitter for Domain Name Generation

Another use of Twitter for malware-related purposes was demonstrated by the Torpig/Sinowal malware. This specimen was programmed with an algorithm for automatically generating new domain names where it would redirect victims for attacks. The bot used Twitter API to obtain recent trending topics on Twitter, and used these topics as part of the seed for its pseudo-random name generator.

According to the Unmask Parasites blog, the bot requested trending topics from Twitter and then used “this information to generate a pseudo-random domain name of a currently active attack site on the fly.” It then injected a hidden iframe that attempted to load malware from that site.

Twitter for Botnet C&C

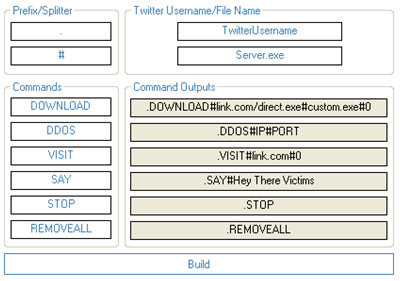

Another example of using Twitter to control malware comes in the form of TwitterNET Builder, which was designed to allow even a notice without programming skills to create a Twitter-controlled botnet. An initial version of this malicious tool was described by Christopher Boyd at GFI Labs, among others.

This bot-creation kit allowed the user to specify the Twitter account name that would be used for C&C, and offered the ability to customize the commands that the attacker would enter as Twitter updates to control the bot network.

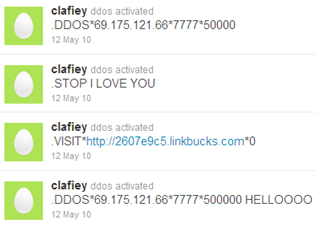

The command set supported instructions to download additional malware to the compromised system, launch a DDoS attack, visit desired URLs, etc. Here's an example of one Twitter account being used to control the botnet created with this tool:

These are just some of the examples of bots using social media for C&C and related purposes. The technologies for retrieving and parsing instructions spread via social media sites are neither new, nor are they advanced. The existence of such malware shows that botnet mechanics follow certain fashion trends, relying upon the same tools and websites that their creator use for regular daily interactions. In the case of social media, attackers are able to control the bots with little interference from security tools while often hiding the instructions and C&C traffic in plain sight.

This note is part of a 4-post series that reflects on malware-related activities on on-line social networks and considers their implications. Other posts are:

- When Malware Distributes Links Though Social Networks

- When Bots Control Content on Social Networking Sites

- When Bots Chat With Social Network Participants